Selling Puts on Margin

A User Friendly Guide to

Selling Naked Puts on Margin

In this in depth exploration of margin and put selling, we're going to cover the following:

- Definition and Explanation of Selling Naked Puts on Margin

- Should You Sell Puts on Margin?

- Selling Puts on Margin to Boost Returns

- Selling Puts on Margin to Hedge Your Portfolio

- Selling Puts on Margin for Convenience

- Selling Puts on Margin for Trade Repairs

- Best and Worst Uses of Margin (Review and Summary)

Part 1 - Definition and Explanation of Selling Puts on Margin

When I'm out and about, I typically drive about 5 mph over the posted speed limit.

First, I feel it's completely safe to do so, and second, I've yet to hear of anyone being pulled over and given a ticket for going 5 mph over the speed limit.

(There are exceptions, of course - when it comes to school zones, residential neighborhoods, and inclement weather, my foot is much lighter on the pedal.)

Selling cash-secured puts is like always driving at or below the posted speed limit and, by definition, means two things:

- You're being paid to insure or offer to buy shares of the underlying stock at a certain strike price by a certain expiration date

- You have sufficient cash to cover the assignment (purchase) of those shares at the agreed upon strike price

In contrast, selling puts on margin - i.e. not having 100% of the cash on hand to cover assignment or delivery of the shares - is a lot like speeding - and how much you speed, a little or a lot, definitely matters.

Understanding Margin - Buying Stock vs. Selling Options

Margin can be used in a couple of very different ways.

First, you can buy stock on margin, or purchase more shares than you literally have the cash for. This is basically a loan from your broker (which your broker will charge you interest for).

You can't, however, purchase options on margin - call or puts - as options are non-marginable in that regard.

Second, margin is also used when it comes to selling non cash secured options. This is not treated as a loan, however, and no interest is accrued or paid.

It's more like a form of collateral - and what's collateralized can be either cash or existing stock holdings (or, obviously, some combination between the two).

For better or worse, selling puts on margin is a way to leverage your capital - either in the form of cash or existing stock holdings - and not pay any interest in the process.

Calculating Margin Requirements When Selling Options

No doubt about it, this can get complicated.

Calculating margin requirements is based on the rules set forth by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Your broker may choose to have different (tighter) requirements than required by regulations, and in periods of extreme volatility, or in the case of individual stocks, your broker may also choose to tighten margin maintenance requirements.

And not all securities are treated equally - stocks with low nominal share prices, leveraged ETFs, etc. will also have much tighter margin requirements.

But to give you an idea of how margin and margin maintenance is determined, here's how TDAmeritrade spells out their Margin Maintenance Requirements:

The Initial and Margin Maintenance Requirement for an uncovered equity option is the GREATEST of the following three formulas:

- 20% of the underlying stock*, PLUS 100% of the option premium MINUS any amount out-of-the-money

- For puts, 10% of the strike price exercise value of the underlying stock PLUS 100% of the option premium value

- For calls, 10% of the market value of the underlying stock PLUS 100% of the option premium value

- $50.00 PLUS 100% of the option premium value

The Initial and Margin Maintenance Requirement for broad-based index options is the GREATEST of the following four formulas:

- 20% of the underlying Index value, PLUS 100% of the option premium MINUS any amount out-of-the-money

- For puts, 10% of the strike price PLUS 100% of the option premium value

- For calls, 10% of the market value of the underlying PLUS 100% of the option premium value

- $50.00 PLUS 100% of the option premium value

The Initial and Margin Maintenance Requirement for narrow-based index options is the GREATEST of the following four formulas:

- 20% of the underlying index value MINUS any amount out-of-the-money PLUS the current market value of the option (premium)

- For puts, 10% of the exercise value of the underlying stock PLUS the premium value

- For calls, 10% of the market value of the underlying stock PLUS the premium value

- $50.00 PLUS 100% of the option premium value

A Much Easier Method - Calculating Option Selling Margin Requirements a Margin Calculator

So this is a pretty neat tool - Cboe Global Markets (which owns the Chicago Board Options Exchange) maintains an option trading margin calculator.

The calculator is Flash based, and gives you a drop down menu to select option strategy type along with a number of other input categories including expiration date, option strike price, option price, and underlying share price.

Do you really need to calculate the margin maintenance requirements of every put you sell?

No, but it can still be useful to get a better feel for how much margin trades actually require.

Don't Forget Option Buying Power

If the above Margin Maintenance Requirement formulas (and margin calculator) indicate how much margin you're using, Option Buying Power basically tells you how much margin you have left.

Investopedia defines buying power as "the money an investor has available to buy securities and equals the total cash held in the brokerage account plus all available margin."

I really like the Buying Power metric.

It doesn't make the margin maintenance math any less complex (the issue isn't the math so much as the multiple formulas you have to consider), but it's a good shorthand method to determine how much margin your portfolio is using at any given time.

That's important because your Buying Power is always going to be in flux since your margin maintenance requirements are going to vary depending on the price of your short options and that of the underlying stock.

So Options Buying Power can function as a speedometer of sorts where you determine a level below which you don't want it to drop. And if it does drop below that level, then maybe it's time to lighten up on some your positions.

We'll look at look at Options Buying Power more closely in Part 3 (Boosting Returns).

Part 2 - Should You Sell Puts on Margin?

If you're new, or relatively new, to writing or selling puts, I would say no for a variety of reasons.

Safer and More Conservative

When it comes to leverage and naked short puts, I recommend you keep everything on a cash-secured basis when first starting out because that's the safest and most conservative route.

After all, when you sell cash-secured puts, the worst case scenario is that you end up owning shares at a price that represents a discount to the open market share price that the stock in question was trading at when you first sold the put.

Hypothetical example: XYZ is trading @ $31/share and you sell a put at the $30 strike price for, let's say $0.50/contract.

What's the worst that could happen?

You end up owning 100 shares of XYZ at an adjusted cost basis of $29.50/share (100 shares assigned at the $30 strike price less the $0.50/contract of premium collected up front).

And if you only sell puts on high quality stocks at strike prices that represent attractive entry points, a worst case scenario really isn't that bad.

When you introduce margin, however, things can get more complicated.

If you don't have 100% of the cash to accept delivery of the shares, you could theoretically find yourself paying interest on shares of a stock that's trading materially below your net entry price.

Or, if that doesn't appeal to you and you want to cut your losses and walk away from the trade, your losses will be magnified.

That's because you used margin to set up a larger trade than what you would've had if you'd set it up on strictly on a cash-secured basis.

Value of Experience

Later on, after you've gained experience selling cash-secured puts, there can be a sensible use of margin (in fact, we're going to be spending much of this article exploring different rationales for selling puts on margin).

But there really is no substitute for experience.

Theory is a great foundation and first step. But it's experience - either direct experience or looking over someone else's shoulders - where the deepest and most profound learning happens.

Pros and Cons of Selling Puts on Margin

If you do have experience selling put option contracts on a cash-secured basis and you're wondering whether it makes sense to incorporate margin to some degree, it's important to understand the pros and cons involved.

The pros are going to vary depending on the put sellers motivation for using margin in the first place. Margin usage can be used:

- To boost your returns

- As a way to hedge a portfolio

- For convenience

- To facilitate naked put trade repairs

And the cons?

There's just one.

Anytime you incorporate margin into your trades, you're adding risk in the form of potentially magnifying your losses if the situation goes to hell and you're not able to navigate, repair, or otherwise fix it.

Option Trading Options - Risk Dial vs. Risk Switch

An analogy I like and use a lot when it comes to option trading and risk is the idea that risk is a dial, not a switch.

There aren't simply two settings where you choose between "high risk" and "low risk." Risk is a spectrum, a dial, a matter of degree, and just about any trade can be made more risky or less risky.

Ultimately, it's up to you how much margin you use (if any), under what conditions, and to what purpose.

And the choices you make will determine how far in one direction or the other your risk dial is set.

Let's explore this in greater depth by considering why a trader might want to sell puts on margin in the first place.

Part 3 - Selling Puts on Margin to Boost Returns

Let's face it - the number one reason why most traders sell puts on margin is to boost his or her returns.

This is not an insignificant amount of returns we're talking about here, and when you run through the numbers, you can see why this can be a very tempting choice.

That's because - and you can check out the margin maintenance formulas above - selling out of the money puts doesn't really use that much of your option buying power. You can rack up quite a lot of short put positions on margin.

But, of course, the question is how smart is it to do that?

Because as we discussed above, option margin maintenance is a dynamic figure and if trades begin going the wrong way on you, your option buying power can quickly plummet as your margin usage increases automatically.

"Use Margin to Get Yourself Out of Trouble, Not Into It"

That's my personal mantra, by the way.

The more margin you use up front to boost your returns, the less margin you'll have for trade repairs. And the more margin you use, the larger the trades may be that require repairs.

Trade repairs?

We'll cover this in more detail on the section that specifically addresses using margin to help facilitate repairing in the money short puts, but in some circumstances, as part of our 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula, we sometimes add contracts to a trade in order to dramatically lower the strike price on an existing position.

Now, there's no rule that says we have to use margin in order to do this.

In fact, because we also initiate small position sizes relative to our portfolio, and because this is a technique that we use sparingly, the need for margin to pull it off is rarely an issue.

But it can be a nice ace in the hole if you ever truly do need it.

I remember a health (and driver's ed) teacher from high school who told the story of how he was driving around town once under icy conditions and how his car was sliding at a very low speed toward a parked car.

No matter how much he pumped his brakes or turned the wheels, the tires wouldn't grip the road and meanwhile, he kept inching closer and closer to the parked car.

He claimed his car was moving so slowly that a pedestrian in front of him could've literally put his hands on the hood and stopped him.

But alas! there was no pedestrian and he only came to a complete stop after he slid into the parked car.

When you really need it, margin can be like having a helpful pedestrian with big hands and good boots to stop you from causing unnecessary damage.

But if you're using margin aggressively to begin with, you're clearly speeding, and you never know when the conditions of the road are going to change.

Unlike actual driving, there's often no warning on Wall Street when inclement weather will hit or when there's a surprise sharp curve in the road.

So the more margin you use when selling puts, the greater the likelihood that you're going to find yourself in a ditch at some point - or worse.

Part 4 - Selling Puts on Margin to Hedge Your Portfolio

Beginning in 2018, inside the Leveraged Investing Club, we began selling calls (in the form of small, conservative bear call spreads) on Limited Upside Situations.

In the same way that we've always sold puts on stocks that we deemed were in Limited Downside Situations (i.e. unlikely to trade lower, or lower by much, in the near term), we started selling calls on stocks we believe were unlikely to trade higher, or higher by much in the near term (Limited Upside Situations).

When you think about it, there's natural self-hedging aspect to selling both puts and calls.

If you have a portfolio of both types of trades with spaced out entry dates and most likely not all expiring at the same time, your entire portfolio isn't vulnerable to a single big market move in one direction or the other.

No Ratios or Formulas

We're not shooting for any kind or arbitrary ratio between short puts vs. short calls/bear calls. We're basically just looking to enter the best new trade we can identify every week or so.

In general, though, there's usually a pretty good mix between both types of trades at any given time. Whether the longer term trend is up, down, or flat, on a shorter term basis, the stock market does a lot of zigging and zagging.

Here's where I'm going with this . . .

I would argue that even if a portfolio used a little margin but had high quality trades of both kinds, it would be safer than a portfolio that didn't use margin but only employed one type of short options.

For example, which portfolio would be lower risk?

- Portfolio A that that uses 125% of its capital trading both (high quality) short put trades and bear call trades (as conditions warrant).

- Or Portfolio B that uses no margin but trades only short puts or only bear calls?

OK - that's a trick question.

The Sleep at Night Strategy, even when it only included short puts, always performed very well.

And, of course, since we're able to repair just about any "bad" short put trade we find ourselves in, it rarely produced any actual losses.

You know - Heads We Win, Tails Mr. Market Loses.

But the point here is that I think you can see how the inclusion of bear call spreads has taken something that was already in the GREAT category and made it even better.

That is, depending on how accurate we are in being able to correctly identify Limited Upside Situations.

But based on our track record, I'd say we've done a very good job in that regard.

Part 5 - Selling Puts on Margin for Convenience

Do successful people ever bounce a check?

Or in the modern, post-check world, swipe their debit card once too often when they don't have sufficient funds in their account?

I don't know about others, but I've certainly done it. I've even had services cut off once or twice when I failed to pay an overdue account.

Note: these were rare occurrences, and it's not because I was broke, it was because I was neck deep in other things, projects, distractions, etc. and simply took my eye off the ball when it came to some of my personal finances.

And as someone who is self employed and trades full time, I don't have an employer who automatically deposits funds into my checking account. Or rather, I'm the employer who does that, and sometimes I forget.

That's where a checking account with good overdraft protection can come in handy.

When it comes to selling puts, margin can be incorporated into your operations in a similar manner - not to accrue debt, but as a matter of convenience.

How so exactly?

A couple of ways . . .

Overdraft Protection

Again, I liken this use to overdraft protection on your checking account.

It's a convenience and designed so that you don't have to worry or always track your account super closely down to the penny.

So maybe your portfolio is fully engaged on a cash-secured basis and a new trade opportunity presents itself.

If you're too legalistic about always being on a cash-secured basis, then you're either going to have to let the new opportunity pass, or you'll have to exit an existing trade earlier than you would've liked to free up capital.

In that way then, a little margin can get you into an attractive trade you otherwise would have to pass on.

Bridging Trades and Opportunities

Similarly, margin can also be used to bridge naked put trades and opportunities.

Let's say you have a trade that's doing very well for you and it's set to expire in a few days, and you're not quite ready to lock in your profits to date. And then you come across another very attractive trade.

The problem?

On a cash secured basis, you don't have the capital to open the new trade without closing the other one.

Or maybe you're in a situation where it's late in the day on a Friday expiration and your position is out of the money and likely to expire worthless. But the stock price is also near the money enough that you'd like to roll the thing out another month and collect another round of money.

You can do that, of course, but a cheaper alternative would simply be to open up a new trade for the next month's expiration a little early rather than rolling the expiring position.

Sure, most brokers treat a new trade and a roll with the same commission base, but you do also pay a smaller fee per contract and, of course, when you roll a short put trade, by definition you are paying something to buy back the old put.

Remember, Mr. Market is everyone in the stock market who isn't you - and that includes market makers and your own broker.

If you're tired of buying Mr. Market lunch all the time, and want to treat yourself every now and then, employing a little margin in these kinds of scenarios is a valid - and not particularly risky - way of doing it.

Part 6 - Selling Puts on Margin to Facilitate Trade Repairs

I referenced trade repair and margin earlier in this article, but it's such an important topic that it definitely needs its own section.

The customized 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula that I personally developed (much of it in a small lab on the campus of the School of Hard Knocks) is an insanely effective and capital efficient trade repair system.

That's because it not only takes the guesswork out of what adjustment to make on a short put trade gone awry, it also tells you the optimum time to pull the trigger.

And it's not a Hail Mary, you've-got-one-shot-to-turn-the-trade-around system. In fact, it doesn't run out of ammo unless the stock itself trades down to zero.

But as part of that trade repair process, under certain circumstances, we will expand a trade by adding more contracts to our trade as a way to aggressively lower the strike price of our in the money position.

Let's look at how that works . . .

The Math - How to Never Lose Money Selling Puts

There's a mathematical principle I like to point out that illustrates how flexible and forgiving writing puts can be.

Here it is: If you have unlimited capital, and the underlying stock doesn't trade down to zero, you should never lose money selling puts.

This is based on another put selling principle - something I call the Double-Half Principle:

In repair situations, by doubling the number of short put contracts you have in a position, you can effectively cut in half the distance between the current share price of the underlying and the strike price of your in the money short put(s).

Huh?

Let's suppose you wrote a $30 put on a stock and then, before you know it, the stock has crashed and burned down to the $20 share price level.

Your $30 short put is now $10/contract in the money. It contains $10/contract of intrinsic value (or $1000 since each contract represents 100 shares of the underlying stock).

And since you wrote the put - i.e. you're short the put - you're short the intrinsic value. You now have a $1000 liability on your trade (plus whatever time value remains on the position, which is not likely going to be very much when the short put is that deep in the money).

But here's the deal - two contracts that are $5/contract in the money have the same total intrinsic value ($5/contract x 2 contracts, or $1000) as your single $30 short put that's $10/contract in the money.

So you can roll or exchange your single $30 short put for (2) contracts at the $25 strike and maybe even get a small net credit if you go out far enough and recapture some time value.

(A net credit on a roll occurs when you receive more for setting up your new short position - put or call - than what it costs you to exit or close out your old or expiring position.)

Intrinsic Value + Time Value

If the overall intrinsic value is identical between (1) short contract that's $10/contract in the money and (2) short contracts that are $5/contract in the money, then generating a net credit simply comes down to how much (more) time value your new position has vs. the old one.

And there are two things that really suck the time value out of an option:

- How far that option's strike price is to the current share price

- How much time remains until that option expires

So it's a pretty safe bet that your new short option position (when using the Double Half Principle) is always going to have more time value than that of your old and expiring one.

That's because your new position, by definition, includes a lot more time and is at a more favorable strike price.

But isn't that risky since you just doubled the size of the trade and it's still not repaired or out of the money?

As always, you want to take everything on a case by case basis.

Do this on a stock like Enron or Worldcom that really does trade down to zero, or do it too early in the process (a big no-no), or do it when you have too little capital to commit, and you're only going to make matters worse.

But realistically, what's riskier?

Is it riskier theoretically being on the hook for 100 shares of a stock at $30/share, or being on the hook for 200 shares of the same stock @ $25/share?

What's more likely to happen - and guaranteed to occur first - the stock rebounding to $25 or the stock rebounding to $30?

And who says you're done working the strike price lower?

In fact, the closer you work the strike price back to the share price, the easier it becomes to continue adjusting the strike price lower without having to resort to adding more contracts.

About That Unlimited Capital Thing:

Let's go back to something I said earlier - about unlimited capital, and how if you had unlimited capital (and assuming the underlying stock doesn't trade down to zero) that there's no reason why you should ever lose money selling puts.

The obvious question - who has unlimited capital?

And the obvious answer is that very few retail investors would be able to raise their hand.

The 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula does include the possibility of or potential for expanding the number of contracts in an underwater trade.

But it's something we use very sparingly and only later in the process and only under specific conditions and as part of a specific timing process.

It's all designed to preserve our capital while getting maximum effectiveness for those times when we do expand an in the money trade.

In fact, in many cases when we add contracts, we only do so once, and sometimes we're even in a position to later reduce the size of the trade.

So we're hardly repeatedly doubling down like a drunken gambling addict at the craps table.

Theoretically, margin could have a role to play in this process

Margin gives you access to extra capital that you don't have, so that can definitely help, but you have to be careful

Because if you use all your margin and the trade still isn't repaired, then you've just made matters worse.

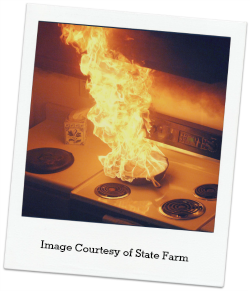

Your Kitchen is on Fire!

In addition to driving above the posted speed limit, margin can also be like having a fire extinguisher.

But if the fire extinguisher is too small - or the fire in the kitchen is too large - then you're going to wish you would have focused on getting all the family members and pets out of the house instead of trying to put out the fire.

Again, my personal mantra is to use margin to get yourself out of trouble, not into it.

Part 7 - Best and Worst Uses of Margin

(Final Thoughts and Review)

The worst use of margin, in my view, is to use it to aggressively boost your returns.

As we've already noted, when you use too much margin up front, there's a potential double whammy effect:

- You place more capital at risk

- You have less capital available for repairs

So it's like getting drunk with your friends and blasting each other with that fire extinguisher as part of the festivities.

If a real fire breaks out, and your extinguisher is empty, you're not going to have any good choices.

If that's the worst use, then what's the best use of margin?

I do think there can be a conservative and sensible use of margin in an option selling portfolio.

And that does include the rationales we've already discussed:

- Incorporating some margin on a hedged portfolio that sells both puts and bear call spreads

- Using margin in the form of convenience

- Having access to margin for trade repairs when necessary

The key, I think, isn't so much what you're using margin for as it is the degree to which you're using it.

I would even go so far as to say that using a little margin to boost your returns a bit isn't the worst thing in the world and a guaranteed recipe for disaster.

Do you remember that Mae West quote?

"If a little is great, and a lot is better, then way too much is just about right!"

That's basically the opposite of what we're talking about here.

The amount of margin you use is arguably more important than the purpose for which you use it.

Selling puts via a small amount of margin for the "vice" of boosting your returns is safer than overleveraging for more noble purposes.

But the use of any kind of margin can be one of those slippery slope kind of things.

When you use a little and nothing bad happens (and, in fact, you only see the benefits) then it can be tempting to use more.

And then some more.

This is where option selling experience can help to ground you and why I recommend those who are new to selling options to avoid margin at first.

If you do decide to sell puts on margin in some capacity, it's a good idea to set up some personal rules and limitations beforehand.

You've got a lot of leeway here - and I see a couple of different ways of tracking (and capping) your margin usage:

- Total Margin Used as a Percentage of Your Portfolio

- Options Buying Power Method

Note: What follows are examples to illustrate, not recommendations of specific target percentages or amounts.

Margin as Percentage of Portfolio

This method is easier to calculate and track because it's a fixed number.

You basically calculate all your open positions to determine how much capital would be required for these to all be cash-secured and then you compare it to your current cash balance.

If, for example, you have a $100K cash balance in your portfolio and you set a limit to sell puts on no more than $125K worth of positions, it's going to be easy to track and monitor.

That personal cap you established ahead of time will let you know when it's time to stop adding new positions.

Or maybe you only tap into margin when conducting trade repairs that require more contracts added to a position. And if you exceed 125% of your portfolio's cash balance, then perhaps that triggers the liquidation of some of your other open, healthier trades.

The greatest risk of margin is that of overleveraging yourself - so that's what you need to guard against the most.

Another method is to incorporate Options Buying Power

Let's assume you have a margin approved option trading account with a $100K cash balance and no open positions of any kind.

At this point, your Options Buying Power would be $100,000 and your Stock Buying Power would be $200,000.

You could set a personal policy to not allow your Options Buying Power to dip below $50K (or to stop initiating new positions if your Option Buying Power dips below that level).

That's still going to allow you to incorporate margin and sell more puts than you otherwise could on a completely cash-secured basis,

As explained earlier, Options Buying Power is a dynamic number that's going to fluctuate depending on the value of your option positions and that of the underlying stock(s).

So in the case of trades that move against you, it's going to give you more of an early warning. It's also a much more precise accounting of how much margin you actually are using in real time.

Finally, there's nothing wrong with always trading on a cash-secured basis!

If you're trading from a retirement account, for example, you have no choice but to sell cash-secured puts.

But that's OK - selling cash-secured puts is a flexible, forgiving, and superior strategy, and you can trade the Strategy your entire life, make a lot of money in a very low risk manner, and never once utilize margin.

You Might Also Like . . .

What to Know About Investing in Stocks on Margin - Great post highlighting the dangers of buying stocks on margin from Joshua Kennon over at thebalance.com.

Tweet

Follow @LeveragedInvest

HOME : Naked Puts : Selling Puts on Margin

>> The Complete Guide to Selling Puts (Best Put Selling Resource on the Web)

>> Constructing Multiple Lines of Defense Into Your Put Selling Trades (How to Safely Sell Options for High Yield Income in Any Market Environment)

Option Trading and Duration Series

Part 1 >> Best Durations When Buying or Selling Options (Updated Article)

Part 2 >> The Sweet Spot Expiration Date When Selling Options

Part 3 >> Pros and Cons of Selling Weekly Options

>> Comprehensive Guide to Selling Puts on Margin

Selling Puts and Earnings Series

>> Why Bear Markets Don't Matter When You Own a Great Business (Updated Article)

Part 1 >> Selling Puts Into Earnings

Part 2 >> How to Use Earnings to Manage and Repair a Short Put Trade

Part 3 >> Selling Puts and the Earnings Calendar (Weird but Important Tip)

Mastering the Psychology of the Stock Market Series

Part 1 >> Myth of Efficient Market Hypothesis

Part 2 >> Myth of Smart Money

Part 3 >> Psychology of Secular Bull and Bear Markets

Part 4 >> How to Know When a Stock Bubble is About to Pop